To Access the Full show, please Login to your Club 19.5 membership: <a href="https://www.theothersideofmidnight.com/club-19_5-login/" title="Sign In">Sign In</a>

Podcast (1sthour): Play in new window | Download (Duration: 1:07:42 — 46.5MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Tonight, we continue our Resurrection Weekend theme with the remarkable story of “the Rainbow Body and Resurrection.”

My guest, Father Francis Tsio, will be relating his extraordinary quest to understand — both religiously and scientifically — the postmortem disappearance of the body of an elderly Tibetan monk, Khenpo A cho, in 1998.

What is a “rainbow body?”

Put simply, it is the manifestation of spiritual attainment in the dozogchen traditions of tantric Buddhism in the Himalayas, involving the literal disappearance of the body after death!

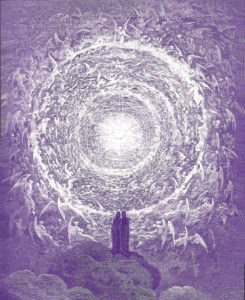

Some have compared this attainment with the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, hoping to answer the question: not only did Jesus rise from the dead … but how did Jesus rise from the dead?

And, yes, we will also be talking once again about the Shroud ….

Adding to our discussion will be “The Other Side of Midnight” regular, John Francis, with his own perspectives on the nature of “the Rainbow Body” … and the resurrection of Christ.

Join us … this Easter Sunday night.

Richard C. Hoagland

Show Items

Richard’s Items:

1- Shroud of Turin inspires professor to create a 3D image of Jesus

2- Farewell, Tiangong-1: Chinese Space Station Meets Fiery Doom Over South Pacific

3- Pope Francis: Church Would Baptize Aliens

4- Vatican Official Declares Extraterrestrial Contact Is Real

Father Francis Tiso’s Items:

1- Jesus on the Cross:

2- Shroud of Turin

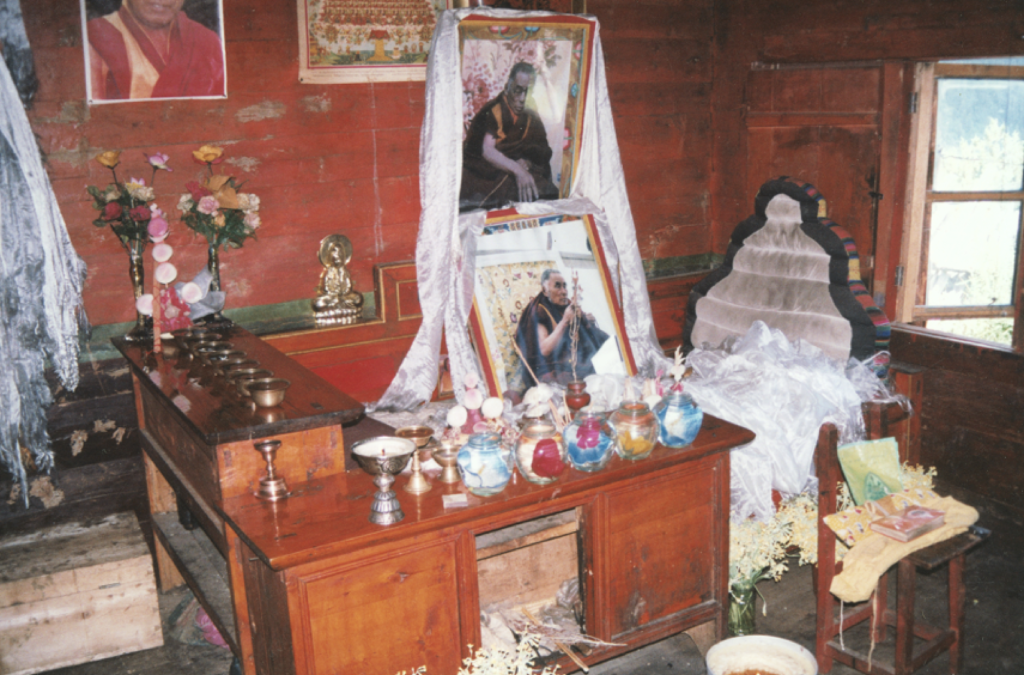

3. Where Khenpo A Chö slept, meditated, and manifested the rainbow body:

4. Khenpo A Chö’s friend, Lama A Khyung (pronounced Chung), who also attained the light body and bodily shrinkage after death.

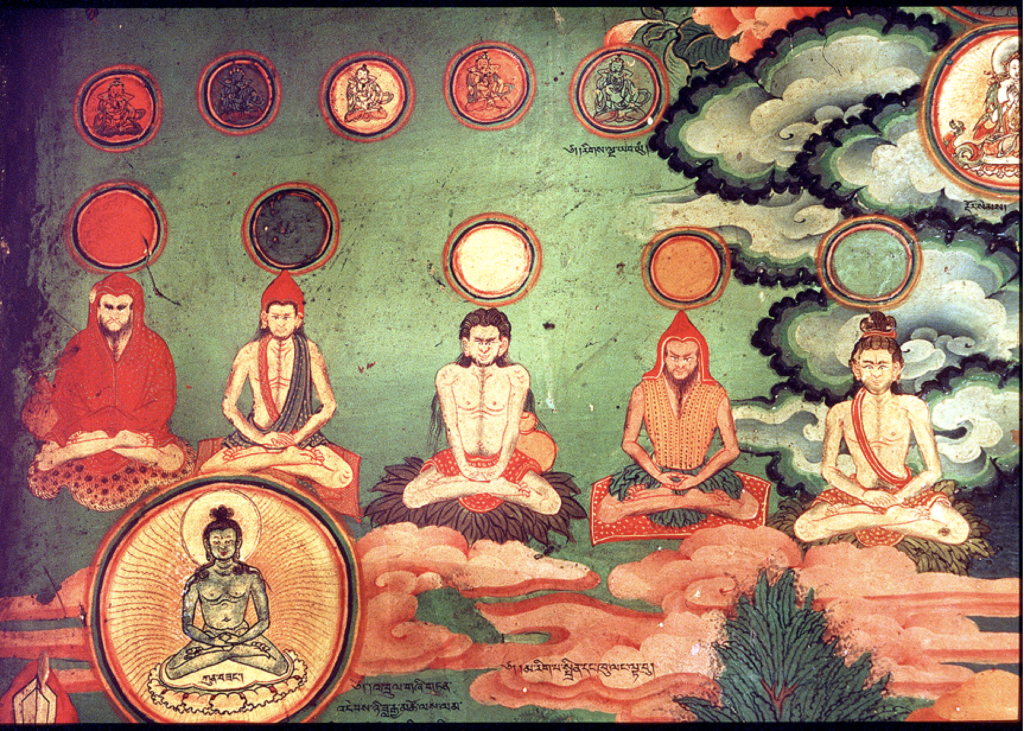

5. Meditation on Spheres of colored light: kLu Khang Temple, Lhasa.

6. A wooden representation of the crucifixion from the 1700s.

7. Khenpo A Chö shortly before his death in 1998:

8- On Rainbow Body and Resurrection:

CLICK ON COVER TO BUY

On Rainbow Body and Resurrection:

1. Thinking of the beauty of a pearl, we tend to forget the irritation in the tender flesh of an oyster that produces those luminous contours. So, too, in the history of religions, we tend to admire the pearls that attract our minds and hearts, but ignore the historical irritations that led to great insights and new pathways. In writing Rainbow Body and Resurrection, I found it necessary to seek for pearls without evading the pains that pearls entail. Like the grain of crystal sand in the tender flesh of the oyster, the claims of resurrection and the attainment of the body of light urge non-mainstream pioneers, today as in the past, into uncomfortable places. In Tibet, the pearl that emerged was a thousand-year history of the rainbow body attainment: after years of practice in the dzogchen form of tantric Buddhism, the yogin’s body may shrink dramatically after death, or even disappear. Rainbows of varied shape, mystic sounds, perfumes, and optical illusions had been reported even in recent times after the death of spiritual masters, such as Khenpo A chö, a monk from eastern Tibet who passed away in 1998.

2. What might the rainbow body be? Put simply, it is a manifestation of spiritual attainment in the dzogchen traditions of the Himalayas involving the postmortem disappearance of the body. At first sight, it would seem that this attainment is on a par with finding the Holy Grail, answering age-old questions of human destiny and the meaning of life. Some might wish to compare this attainment with the resurrection of Jesus, hoping to answer the question: not only did Jesus rise from the dead, but how did Jesus rise from the dead? The implications of any attempt to answer these questions are a challenge to all the religions involved, and to the criteria of modern science as well. If the phenomena reported- bodily shrinkage and disappearance, preternatural phenomena, and postmortem appearances- are not reducible to pious symbolism, it would seem that the world needs to take another look at the contemplative traditions that have been under assault for the past five hundred years of history. Only those who are willing to undergo a long and arduous period of training and retreat are able to access this attainment. Such training requires membership in the kind of institution that has been brutally dismantled by official ideologies East and West for centuries. Is modernity once again just plain wrong- an obstacle to the full realization of human potential? My research suggests that claims about the rainbow body attainment arose in the context of a crucial historical moment in which contemplative disciplines met in intimate dialogue, under nearly ideal circumstances in the eighth century. Within a few centuries, the circumstances of sectarian competition within Tibet required an even more emphatic representation of these claims, which are not acceptable to all schools of Buddhism. Significantly, Khenpo A chö’s life straddles two of these schools a bit uncomfortably, generating the irritation that entices our inquiry.

3. When I first heard about the postmortem disappearance of the body of an elderly Tibetan monk, Khenpo A chö, in 1999, it was not the first time that I had heard of the “rainbow body” among Tibetan saints. I had already been working for fifteen years on the story of Milarepa, whose body is said not to have left bodily relics after death. My spiritual father, Br. David Steindl-Rast, a Benedictine monk long known for his dialogue with Buddhists, urged me to go to Tibet to find out more about Khenpo A chö, his life, death, beliefs and disciples. Br. David was convinced that a contemporary paranormal manifestation like the rainbow body, as reported for the Khenpo, might shed light on the debated question of the historical veracity of the resurrection of Jesus.

4. In the summer of 2000, I had enough grant support to go first to Dolpo in Nepal to attempt a catalogue of the sacred paintings of the temples of the Tarap Valley, at an altitude of 4200 meters. In the weeks afterwards, proceeding by land cruiser from Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province in the PRC, my team was able to visit the towns of eastern Tibet (Khams) where Khenpo A chö led most of his life. At an altitude of about 3500 meters, our research was less physically demanding than the Dolpo trek, and we were grateful to have acclimatized before arriving in Khams. Interviewing lamas, disciples and relatives of the late Khenpo required unusual linguistic skills, careful diplomacy, physical stamina and a great deal of clear-eyed decision making on site. I compiled a set of questions in Tibetan with the help of a colleague who had tutored me in my 1997 expedition, and was accompanied by a fluent Tibetan speaker from the University of Virginia Tibetan Studies program, Douglas Duckworth. The answers we received during interviews in the Khenpo’s hermitage and later at the Mindrolling Monastery in northern India, led us to seek more deeply for the wellsprings of the practices known as “the great perfection” (dzogchen)- or perhaps “the pearl of great price”.

5. Over the next fourteen years, I compiled as much information as I could on dzogchen, on the mysticism of light in various religions, and on the spiritual byways of Central Asia in the heyday of the Silk Road. While I was reflecting on these topics, other scholars were publishing groundbreaking studies of the manuscript discoveries that would enable me to find my way into the root system of the great forest of Central Asian spiritual and contemplative schools. I had already discovered translations of the Arabic and Syriac spiritual teachings of the controversial speculative mystic John of Dalyatha, who just happened to have lived in the eighth century, the height of the Tibetan Empire. Fragments of lost Christian monastic meditation techniques about experiencing spheres of mystical light and bodily transformation seem to resemble the earliest dzogchen teachings from imperial Tibet. Other ancient manuscripts from Central Asia describe Buddhist visualization techniques nearly identical to those used to this day in dzogchen practice. New translations of the Chinese Christian documents that had been found at the Central Asian desert oasis of Dunhuang enabled me to show how the spiritual teachings of the Syro-Oriental Church had encountered Chinese Buddhist wisdom. From the same Dunhuang cache emerged new insights about the origins of the dzogchen approach to Buddhist tantra. Woven across the Silk Road were shared narratives that both concealed and revealed some remarkable conversations. The life of Garab Dorje turns out to be the nineteenth sura of the Qur’an (the story of Jesus and Mary), adorned with Indian tantric ornaments, dancing like the masked monks in a Tibetan opera. In this same time frame, the eighth century, spiritual astronauts of the Silk Road era – Indian, Chinese, Oriental Christian, and Japanese – were sharing ideas in Hsian, the capital of Tang China. With this knowledge, it becomes possible to connect the dots linking Islam, Christianity, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Indian yogic systems and the Buddhisms of India, Tibet and China, with particular attention to the fertile ground and tender flesh of eighth century Central Asia. The rainbow body and the resurrection seem to have met at some point in these almost unimaginable milieux of spiritual sharing and contemplative competition.

6. In recent years, with an increasing interest in Tibetan religion, various relics purporting to be the preternaturally shrunken bodies of such yogins have been displayed for veneration around the world. It is no longer possible to dismiss the phenomenon as folklore. Now the “begged question” is: How does one do credible research on a preternatural phenomenon? The book Rainbow Body and Resurrection, proposes a number of guidelines and criteria for such research, mindful that the researcher’s self-awareness and purpose may have crucial roles to play in the emergence of the luminous contours of the long-sought precious pearl.

Father Francis V. Tiso

Father Francis V. Tiso was Associate Director of the Secretariat for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops from 2004 to 2009, where he served as liaison to Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, the Sikhs, and Traditional religions as well as the Reformed confessions.

Father Francis V. Tiso was Associate Director of the Secretariat for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops from 2004 to 2009, where he served as liaison to Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, the Sikhs, and Traditional religions as well as the Reformed confessions.

Before coming to the USCCB, Father Tiso was assigned to the Archdiocese of San Francisco where he served as Parochial Vicar of St. Thomas More Church and Chaplain at San Francisco State University and the University of California Medical School. He was also Visiting Professor in the Archdiocesan School of Pastoral Leadership, where he taught courses in Foundational Theology. He also served as Parochial Vicar in Eureka, CA and in Mill Valley, CA.

A New York native, Father Tiso holds the A.B. in Medieval Studies from Cornell University. He earned a Master of Divinity degree (cum laude) at Harvard University and holds a doctorate from Columbia University and Union Theological Seminary where his specialization was Buddhist studies. He translated several early biographies of the Tibetan yogi and poet, Milarepa, for his dissertation on sanctity in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. He has led research expeditions in South Asia, Tibet and the Far East, and his teaching interests include Christian theology, history of religions, spirituality, ecumenism and interreligious dialogue.

Father Tiso is a priest of the Diocese of Isernia-Venafro, Italy. He is Diocesan Delegate for Ecumenical and Inter-religious Affairs. He was also chaplain of the well-known Hermitage of Saints Cosmas and Damian at Isernia from 1988 to1998. He is now chaplain to the migrant communities in this part of Italy, and founder and president of the Association “Archbishop Ettore Di Filippo,” which offers work training, language skills, and intercultural experiences. See: www.asdarciettoredifilippo.it

Father Tiso has written and lectured widely. He has traveled extensively in India, Nepal, Tibet, Thailand, Japan, and Bangladesh. He is the recipient of grants from the American Academy of Religion, the American Philosophical Society, the Palmers Fund in Switzerland, and the Institute of Noetic Sciences in Petaluma, CA. He is a musician and paints in acrylics and watercolors.

His research on Milarepa, Liberation in One Lifetime, was published in 2014, and he has recently published an article on Milarepa’s teachings on the intermediate state (the “bardo”). Tiso’s most recent book, Rainbow Body and Resurrection (2016), explores the background to the manifestation of postmortem dissolution of the body in the case of Khenpo A Cho in 1998 in eastern Tibet.

John Francis’ Items:

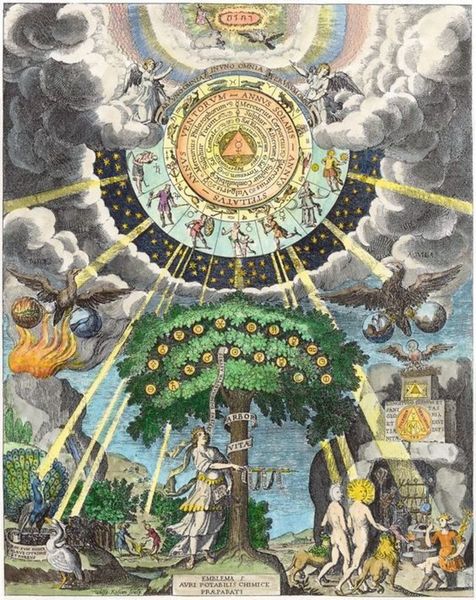

1) Temptation Seal

2) Tree of Life

3) Radiant Love C

LICK ON COVER TO BUY

5) 4 Literally Awesome Facts About Our Lady of Guadalupe …

http://mtncatholic.com/2014/12/11/4-literally-awesome-facts-about-our-lady-of-guadalupe/

John R. Francis

John R. Francis is a retired college mathematics professor who specialized in statistics and experimental design. He also has degrees in physics and psychology. In the early 1970’s he served in the Pacific Seventh Fleet as a U.S. Naval Officer aboard a guided missile destroyer.

John R. Francis is a retired college mathematics professor who specialized in statistics and experimental design. He also has degrees in physics and psychology. In the early 1970’s he served in the Pacific Seventh Fleet as a U.S. Naval Officer aboard a guided missile destroyer.

In 1975 he had a profound near-death experience that permanently expanded his mind out of its previous limited, rational boundaries. He now views life as a highly purposeful and multidimensional, evolutionary expression of one universal consciousness.

His areas of metaphysical expertise include sacred geometry, spiritual self-defense and heart-centered meditation. Furthermore, he has deciphered numerical codes that unlock the deepest secrets of key religious scriptures. John is the author of “The Mystic Way of Radiant Love.” https://www.centerforworldnetworking.org/newsletter/1610.pdf

Kynthea Item: Kalu Rimpocheabout (on the right) 2 weeks before he passed. Notice how joyful he is! He was of the Kagyu lineage and also practiced Dzogchen and ah Mudra.